‘Myth is a story that implies a certain way of interpreting consensus reality so to derive meaning and effective charge from its images and interactions. As such, it can take many forms: fables, religion and folklore, but also formal philosophical systems and scientific theories.’ Bernardo Kastrup, More Than Allegory: On religious myth, truth and belief (2016).

Faerie-tales are a type of mythology. They have spent much time debased to the level of children’s stories; just amusing tales pulled up from an archaic folkloric past that bear little relevance to a modern society saturated with every imaginable storytelling media, from IMAX to Xbox. But if we just give them a chance and scratch the surface a little, they begin to offer up and to demonstrate something much deeper: meaning. And anything that offers to demonstrate a deeper meaning to existence should probably be valued, in a world where meaninglessness seems to have become endemic.

The best faerie-tales are never one-offs, but seem to cluster as a single form from many sources, which are dispersed geographically and chronologically. In Europe and America they were mostly collected by folklorists in the 19th and early-20th centuries, from both oral and written sources, and then disseminated from there. But where did they come from, and more importantly, why were they there in the first place?

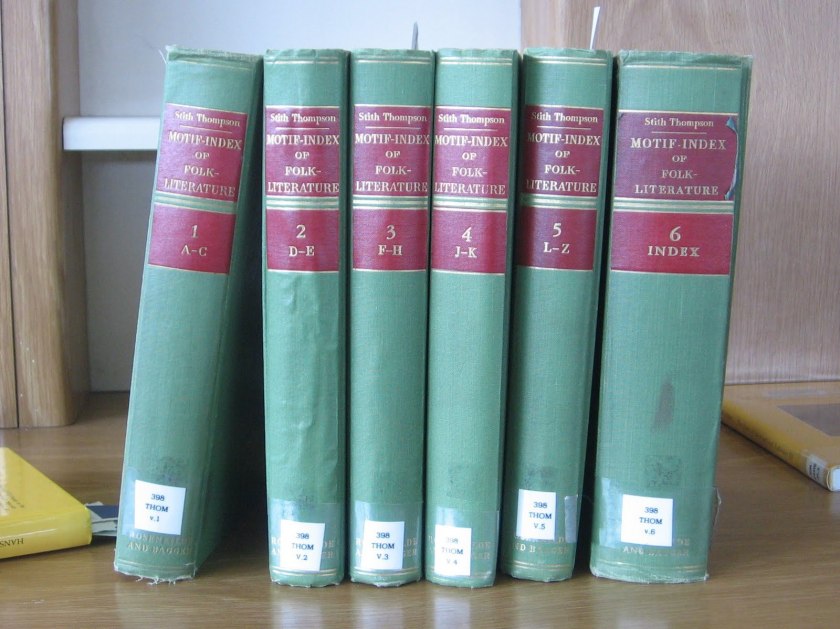

The Aarne-Thompson catalogues of folktale types and motifs were first put together in 1910 by the Finnish folklorist Antti Aarne and completed by Stith Thompson in 1958. They consist of several doorstop volumes, which index every conceivable story type and motif from around the world. It’s been suggested that the catalogues actually codify every human experience, distilled into story. Anyone brave enough to venture into this multi-volume information overload soon realises that they are capturing something special; an index of our collective memory as a species, realised through the medium of mythology. And after all, what is our collective memory apart from the storytelling of mythology? Amidst the catalogues are the story types classed as faerie-tales, each containing hundreds of separate motifs; they are the descriptors of a vast array of myth. And once we head off to find the actual stories outlined in the catalogues we soon discover that they are packed with meaning at many levels. These are not simple tales told to pass the long winter nights (although that was always one use for them), but rather, they are sophisticated tools that can be used to interpret human experience and to help understand the reality we find ourselves in.

So if we hone down to pick up a folktale type with its motifs from the Aarne-Thompson catalogue, we can find a story and use it as an example — a case study to explain what a faerie-tale might tell us about ourselves and our beliefs. Type ML-4075 is ‘Visits to faerie dwellings.’ Add some motifs such as ‘Faeries made visible through use of ointment’ (F235.4.1) and ‘Faeries take human nurse to care for faerie child’ (F372), then we can narrow things down to a distinct group of folktales containing these elements, from India, Russia, Scandinavia, Lithuania, Britain, France and Ireland; all with their own idiosyncrasies but quite clearly from the same story-stock. The narratives suggest a relatively short gestation period before being collected in the 19th century and catalogued in 1910, although many of the story elements do seem to incorporate much older themes (Gervase of Tilbury records some of the motifs in a 13th-century French story). And the stories wide geographical dispersal suggests the messages they hold have a universal quality — their geneses seem to be local and organic, but tapping into an unknown non-local source. My favourite is one of the Cornish versions collected by the folklorist Robert Hunt in 1865: Cherry of Zennor. It goes something like this:

The time-setting is mid 19th century. Cherry is sixteen and lives in the village of Zennor on the north Cornish coast with her family in respectable poverty. She heads off to seek a job in service, but lethargy and a certain work-shyness get the better of her and she sits down for a mope on the moors, next to an ancient stone cross. Out of nowhere a well-dressed gent appears, flatters her, flirts with her, and tells her he’s a widower and wants her to come to his home, where there is a child to look after. She agrees enthusiastically. There is an interesting sequence where they walk what seems to be miles, but always downwards and through sunken lanes where the overhanging trees formed a tunnel-like descent. The house and gardens are beautiful and so is the little boy, who is to be Cherry’s charge. Unfortunately, for Cherry, the ex-mother in law is still hanging around and she’s a surly sort, who goes out of her way to make Cherry’s life difficult.

Here we are introduced to the magic ointment, which Cherry has to balm the child’s eyes with each morning. She is advised by the mother in law to never apply it to her own eyes (I think you’ll guess what might happen later with that loaded concept). The old woman then takes Cherry through dark corridors in the house (another tunnel-like journey) into a forbidden room, where there are (bizarrely) a group of human statues, some complete, others not. The insinuation is that they’re real humans turned to stone. When Cherry is ordered to polish a ‘coffin-like box’ containing one of the statues, they start to come to life. Quite reasonably, Cherry faints, a ruckus is caused and the master turns up. He kicks out the mother in law, forbids Cherry to enter the room again, and then turns on the charm for a few days, kissing and flirting with Cherry in the garden.

All’s well for a while — Cherry looks after the child, gets her romance-lite and is generally enamoured with her new life. But when she — inevitably — decides to use the ointment on her own eyes things take a change for the weird: “Everything now looked different about the place. Small people were everywhere, hiding in the flowers sparkling with diamonds, swinging in the trees, and running and leaping under and over the blades of grass.” She sees the master playing with some of the little ladies in a well, and then the following evening spies him in a surreal musical communion with the stone statues through the keyhole of the forbidden room, where sure enough they had all come to life.

So the next day, when he comes on hot with some hanky-panky, she slaps his face and tells him what she saw and how jealous she’s been. That’s the end of the road for Cherry — her use of the ointment and her betrayal of trust means she has to go home. The master takes her back (uphill through the tunnel-like sunken road) to the downs and cross where she first encountered him and leaves her there. She wails for a bit and then returns home (more time has passed here than in her faerie home) with a story no-one believes. Her remaining life consists mostly of depression and hanging out on the downs hoping to see the master again. But he never comes.

Full text from Robert Hunt, Popular Romances of the West of England

In some of the other variations of this story, the girl encounters the master (or the mother in law) again, usually at a market or fair, and when she is asked which eye she sees him with he blinds her in that eye, and she sees faeries no more.

But what can be made of this strange story? What does it mean? Time to apply some interpretations…

- A reductionist-materialist interpretation This interpretation might see the whole story as a load of baloney, predicated on deluded rustics making it all up from fevered imaginations and promulgating it to the gullible by way of fireside stories over the years, until some gentleman folklorist turned up and recorded it. This is the rigid interpretation to be expected of a modern Western sceptic, but it doesn’t explain the commonality of the story type and motifs over a wide geographical area without mass communication. It also suggests a worldview that has become tightly dogmatic and refuses to accept meaning or reality in anything that does not adhere to its own self-built belief-system based on a universe knowable only through the scientific method. Aldous Huxley called this the disenfranchisement of consciousness. But then such is the world we live in.

- A Jungian interpretation As usual, Carl Jung, and adherents to his psycho-mystical outlook, have much more interesting things to say. A Jungian analyst would immediately start looking for archetypes, mythological themes common to humanity, which find their way into these types of folkloric fables for the purpose of teaching us something about existence. According to Jung, these archetypes reside in the Collective Unconsciousness of humanity — the sum total of all knowledge and memory stored in a transcendent Mind, accessed through dreams, stories and mythology. They would find plenty of archetypes in Cherry of Zennor. One archetype is the need to understand that the breaking of social taboos has consequences. This is a universal archetype, that can be applied in most social groups as a life lesson. Cherry breaks the taboo of using the ointment as well as the prohibition against looking into the forbidden room. If she’d kept her mouth shut about seeing the master playing music with the animated stone statues and playing with the faerie ladies in the well, she might have been allowed to stay in faerieland. But that was never going to happen — the story is aware to the fact that people cannot expect to get away with breaking conventions that seem to have a higher purpose, even when that purpose is never explained… it’s just the way of things. It may seem culturally conservative, but it is a lesson embedded in the story. It’s a reinforcement of social mores, disguised within the narrative; a subliminal message based in the collective experience of humanity. Likewise, the innocent maiden, the critical old woman, the all powerful master, and the opportunity to see reality behind the illusion — all are archetypes that can be applied as metaphors and analogies back in the consensus reality of the listener to the story. But a Jungian interpretation such as this requires us to accept that there is a Collective Unconscious that is being tapped into for the purposes of spreading the knowledge contained therein through the telling of faerie-tales. This Collective Unconsciousness is an alluring and convincing idea that finds its way into many philosophical, psychological and scientific theories of how things work for us. But for now its complexity and mind-boggling nature might need to wait for another time… although if you’re interested, this is a good intro. to Jung’s Collective Unconscious.

- The faerie-story is a dream This allows common ground between followers of the first two interpretations. Jung would have been happy to contend that the archetypes in faerie-stories may have originally surfaced in dreams, but also that this would not detract from their value as tools for understanding consciousness. For a Western sceptic, a dream is simply another type of epiphenomenon produced in the brain for no particular reason. Its subsequent retelling as a faerie-story can be safely reduced to meaninglessness. But once again, the commonality of the story type and motifs through space and time sits happier with a Jungian interpretation. Whether it started as a dream or dreams isn’t as important as where the dream/s came from in the first place, because those dreams are plugging into the Collective Unconscious and sending us messages to learn from. There are certainly dreamlike elements to the story, most especially the statues coming to life and the sudden appearance of a bunch of humanoid entities at the application of some ointment to the eyes. This does give some clout to the dream-made-into-story interpretation, but only if we accept that the widespread geographical sources of this story type have a collective source for the dreams.

- The story is a retelling of events experienced in an altered state of consciousness Once more, this interpretation is dependent on a single type of experience finding its way to lots of people in dispersed locations and in different times, before modern means of mass communication. But its an interpretation of faerie-tales that has begun to gain a lot of traction in recent times, best articulated by Graham Hancock. The basic premise is that when, for whatever reason, we enter an altered state of consciousness, we contact different realities than the one we normally experience. The altered state can be brought about by ingesting chemicals, meditation, trauma, excessive physical exertion, disease and illness, or even spontaneously without any apparent reason. We could also include the dreams from interpretation number 3 as an altered state, as it is the most common way humans experience a fundamentally different reality . Once the mind is in the altered state the usual physical rules of the universe no longer apply and anything can become possible. Cherry’s story certainly includes many components of various induced altered state of consciousness: moving through a tunnel, time dilation, humanoid entities appearing suddenly, non-organic lifeforms, entering a beautiful landscape, and even depression on return to normal reality. Adherents to a reductionist interpretation would be able to agree this is a viable interpretation, but would also remind us that everything experienced can be written off as an hallucination, explained by changes to brain chemistry. However, anyone who has experienced an extensive altered state of consciousness beyond a dream, will be able to associate with the super-reality of the experience. There can be a sense of touching something every bit as real as regulation reality. What the mind finds there can be brought back, in this case in the form of a faerie-story. The two motifs of the faerie ointment and the potential traumas Cherry experiences, such as weeping on a desolate moor, are embedded clues as to the means of her reaching the altered state of consciousness. There’ll be a blog post going into detail on this possible interpretation for the interaction with faeries very soon. Meanwhile, here’s the late, great Terence McKenna talking about faeries and DMT: The DMT experience, with faeries included.

- The story really happened This interpretation might reside comfortably with the altered state of consciousness theory. If it’s accepted that perceived reality can be achieved through a variety of consciousness states, then what really happens can be extended beyond experiences in five-sense reality. However, the insinuation of interpretation number 5 is that the world of faerie has been encroaching on our consensus reality and interacting with it at a material level. If that’s the case, then where is that world, how is it crossing over into ours, and why is it doing so? I’ll talk about the Quantum Mechanics of faerieland in a future blog post, but for the purposes of this discussion, it is worth mentioning that certain current quantum theories suggests that in order for our physical universe to operate as it does, we are required to take into account at least seven extra dimensions of reality, and perhaps many more. These enfolded dimensions exist as implicate spaces, that can presumably hold many different forms of reality than the one we accept as the absolute reality (who lives in the 11th dimension?). If this is the case, then what resides in these dimensions may be able to seep through to ours when the conditions are right. It might be difficult for most people brought up on a diet of classical, materialistic Western science to stomach such a proposal, but in the wackadoo-world of quantum physics the unbelievable is the usual, and our entire universe is made up of this crazy sub-atomic reality where time doesn’t seem to exist, and no particles are present until someone observes them. Compared to some of the current mind-bending scientific theories about the way our universe works, a parallel faerie world only slightly tweaked from the one we seem to live in, and interacting with it, begins to look a lot less insane.

So what do we conclude? There is probably much truth in all five interpretations, and certainly much overlap. We could also greatly expand the interpretations here and add further theories (how about the theory from Solipsism that suggests that the story does not exist at all until you the observer come across it and allow its subsequent creation in your own conscious awareness). But hopefully, it is clear that faerie-tales such as Cherry of Zennor hold depths of meaning within them; coded meaning that just needs unscrambling to reveal some secrets direct from faerieland. It’s a strange place… but then reality is strange.

To finish, you might like to try this very trippy faerie cartoon from the 1970s. It’s highly odd, but made by people who demonstrate great attention to faerie detail.

Really interesting analysis. I hadn’t heard of Cherry before, but read similar tales. I’ve recently read some short stories which engage with magic and language and made me think in a similar way. (Under My Hat: Tales from the Cauldron by J Strahan, in case you didn’t have anything else to read)

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another explanation is that she entered another dimension that has its own people that can see us but we can’t see them.

LikeLike

Very interesting site Mr. Rushton. Keep on posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person