“Faerie is a world of dark enchantments, of captivating beauty, of enormous ugliness, of callous superficiality, of humour, mischief, joy and inspiration, of terror, laughter, love and tragedy. It is far richer than fiction would generally lead one to believe and, beyond that, it is a world to enter with extreme caution, for of all things that faeries resent the most it is curious humans blundering about their private domains like so many ill-mannered tourists. So go softly – where the rewards are enchanting, the dangers real.” Betty Ballantine from the foreward to Faeries by Brian Froud and Alan Lee.

This is a chronological trawl through the multifarious artwork that has attempted to visually display the faeries. This art is so diverse and wide-ranging that I can only hope to incorporate a small fraction of the whole, but it will hopefully give a flavour of the changing nature of the artistic representations of these ultra-dimensional entities, that appear to have been flitting around our collective peripheral vision for millennia. Much of it has been produced by people who have, in one way or another, managed to alter their states of consciousness to see beyond the material world, dispatch their rational mindset, and experience the surrogate realities that occasionally coincide with the sensory world we usually presume to be the real one. From prehistoric cave art to modern depictions of amorphous nature spirits… it’s quite a trip…

Prehistoric Cave and Rock Art

Our earliest known artistic portrayals of the world, and how human consciousness interacted with it, come in the form of cave paintings from all parts of the globe, starting c.35,000 BCE (see Shamanic Explorations of Supernatural Realms: Cave Art – The Earliest Folklore for a detailed look at cave paintings as folklore). Many of these cave paintings include humanoids and therianthropes, otherworldly entities that have been recorded alongside geometric imagery, stylised animals and landscapes. But what state of mind were our Palaeolithic ancestors in when they were painting these strange entities in often difficult to access caves and shelters?

The anthropologist David Lewis-Williams has made the convincing argument that these cave and rock-shelter paintings were produced by shamanic cultures to represent reality as perceived in an altered state of consciousness. Twenty years ago this idea was anathema to anthropologists, but since the work of Lewis-Williams, and many others, the theory has tipped over to become an accepted orthodoxy. There are hundreds of motifs (such as entoptic swirls, dot patterns and spirals) in the cave paintings that correlate with the visionary states of people in an altered state of consciousness, brought about most especially by the ingestion of a psychotropic substance. The basic premise is that the shamans of these Palaeolithic cultures transported themselves into altered states of consciousness and then painted the results of their experiences on the walls of caves and rock shelters — experiences that frequently included therianthropic beings and supernatural humanoids that correlate in many ways with later faerie types.

In his 2005 book Supernatural, Graham Hancock makes extensive use of Lewis-Williams work, as well as his own ethnographic studies, to investigate further into the concept of cave art as shamanic recording of different realities through altered states of consciousness. Hancock suggests it was no accident that these cave paintings began to

appear when they did, that is between 30-35,000 years ago, just as anatomically and neurologically modern humans asserted their predominance across the Palaeolithic world. He goes as far as to propose that the cultures these peoples instigated were fundamentally predicated on an understanding of the world and reality brought about by mind-altering psychedelic plants and mushrooms. A reductionists’ view would assert that whilst shamanic cultures may be accessing a subjective hallucinogenic reality, this reality is simply delusional, the result of neurophysiological changes brought about by chemical changes in the brain, as a result of the ingestion of psychotropic compounds. The ‘entities’ portrayed in the cave paintings are all simply conjured up by compromised human minds. But recent research (with Graham Hancock at the forefront) disputes this view. There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that much historic folklore can be related intimately to the type of stories being told in cave art by Palaeolithic shamans, with which the descriptions are often remarkably similar.

This preliterate artwork could be seen as the earliest folklore, encapsulating stories and experiences now lost to us. The entities represented in caves and rock shelters throughout the world certainly meant something to the artists creating them, and would have been recognised by all who viewed them as part of the reality they inhabited, in whatever state of consciousness that might have been. We can perhaps imagine the caves and rock shelters as places where folk-stories were conveyed, using the imagery as a medium to enhance the tales, made especially effective in some of the caves, where the only light would have been from the flames of torches. The difficulty of access to many of these spaces suggests that whatever these images represent, they must also have had a highly significant ritualised purpose to the people viewing them. Whilst we cannot retrieve the stories they told, we can recognise that the artwork must have been fully integrated into the cultures of which they were a part, especially as we are probably seeing only the surviving fraction of what originally existed.

Classical and Medieval Faeries

In Ancient Greek culture there was a well-classified pantheon of nature spirits, sometimes termed Dryads (Δρυάδες) and Hamadryads (Ἁμαδρυάδες), but often given the general term of Nymphs (νύμφη). They were female tree spirits, that were usually recognised as being one with the tree, protecting it with their vitality and receiving symbiotic protection and life in return. Pausanias, in his 2nd-century Description of Greece, although distancing himself from the belief, says: “Those Dryads who in days of old, according to the story of the poets, grew out of trees and especially out of oaks.” Some Hamadryads life spans were directly related to the trees, and although usually temperate and kind in nature, they would deal retribution on any person destroying or damaging their trees and habitats, often with the help of the gods.

Most surviving depictions of nymphs are from stone reliefs and statues (and occasionally in mosaics), often shown as dancing or in relation to gods and goddesses, most frequently the nature god Pan, whose pan-pipes were even part-fashioned from the shapeshifted nymph Syrinx, who had been turned into a reed by her sisters to avoid his amorous advances.

It is clear the ancient Greeks (followed by the pre-Christian Romans) regarded these named and categorised nature-entities as metaphysical representatives of an otherworld, who would only interact with humanity during certain conditions. In this they are faeries in all but name – seen through the cultural lens of classical Greek and Roman civilisations.

Such statuary and reliefs are important to the radical but intriguing theory put forward by the philosopher Julian Jaynes in his 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Jaynes asserts that consciousness did not arise far back in human evolution but is a learned process based on metaphorical language. Prior to the development of consciousness, Jaynes argues humans operated under a previous mentality he called the bicameral (‘two-chambered’) mind. In the place of an internal dialogue, bicameral people experienced auditory hallucinations directing their actions, similar to the command hallucinations experienced by many people, such as schizophrenics, who hear voices today. These hallucinations were interpreted as the voices of the gods or other metaphysical entities, such as the nymphs. In Jaynes’ theory the visual images of otherworldly beings were fundamental as conduits for providing instructions and oracular advice to bicameral people:

Such statuary and reliefs are important to the radical but intriguing theory put forward by the philosopher Julian Jaynes in his 1976 book The Origin of Consciousness in the Breakdown of the Bicameral Mind. Jaynes asserts that consciousness did not arise far back in human evolution but is a learned process based on metaphorical language. Prior to the development of consciousness, Jaynes argues humans operated under a previous mentality he called the bicameral (‘two-chambered’) mind. In the place of an internal dialogue, bicameral people experienced auditory hallucinations directing their actions, similar to the command hallucinations experienced by many people, such as schizophrenics, who hear voices today. These hallucinations were interpreted as the voices of the gods or other metaphysical entities, such as the nymphs. In Jaynes’ theory the visual images of otherworldly beings were fundamental as conduits for providing instructions and oracular advice to bicameral people:

“… early civilisations had a profoundly different mentality from our own, that in fact men and women were not conscious as we are, were not responsible for their actions, and therefore cannot be given the credit or blame for anything that was done over this vast millennia of time; that instead each person had a part of his nervous system that was divine, by which he was ordered about like any slave, a voice or voices which indeed were who we call volition and empowered what they commanded and were related to the hallucinated voices of others in a carefully established hierarchy.”

With the Christianisation of Europe in the Middle Ages the faeries became co-opted by the Church as representations of demonic entities on Earth. In order to counter an evident vernacular belief in faeries, the Church’s official line was that the faeries were the result of delusions orchestrated by the Devil and his evil minions for various nefarious purposes. This was (from 1184) reinforced by The Inquisition, which could include questions in its commissions about any interactions with the faeries, aimed at weeding out heretical beliefs and punishing the perpetrators. Hardline preachers were very clear on what people needed to believe when it came to the faeries:

“There are also others who say that they see women and girls dancing by night whom they call elvish folk, or faeries, and they believe that these can transform both men and women or, by leaving others in their place, carry them to elf-land; all of these are mere fantasies bequeathed to them by an evil spirit.” Wycliffite sermon c. 1390.

Richard Firth Green, in his 2016 book Elf Queens and Holy Friars , digs deep into the  medieval vernacular belief in faeries, mostly by utilizing the surviving texts of mystery plays, to demonstrate that there was a widespread acceptance of the faeries as a supernatural race of beings who interacted with humans on a regular basis. He makes the convincing argument that this was a popular cultural reaction to the ecclesiastical conception of faeries as minor-demons. Many of the mystery plays (which were performed in villages and towns throughout medieval Europe) incorporated faeries as plot devices, with the assumption that the audience would know exactly who they were, and that they were not demons, but rather arbiters of a supernatural realm that was neither heaven nor hell. However, the faeries rarely made it into medieval artwork without being mutated into demons. It took the Renaissance to reestablish them as an integral species of otherworldly characters within works of art.

medieval vernacular belief in faeries, mostly by utilizing the surviving texts of mystery plays, to demonstrate that there was a widespread acceptance of the faeries as a supernatural race of beings who interacted with humans on a regular basis. He makes the convincing argument that this was a popular cultural reaction to the ecclesiastical conception of faeries as minor-demons. Many of the mystery plays (which were performed in villages and towns throughout medieval Europe) incorporated faeries as plot devices, with the assumption that the audience would know exactly who they were, and that they were not demons, but rather arbiters of a supernatural realm that was neither heaven nor hell. However, the faeries rarely made it into medieval artwork without being mutated into demons. It took the Renaissance to reestablish them as an integral species of otherworldly characters within works of art.

Early Modern Faeries and Witches

Between the 16th and 18th centuries both ecclesiastical and secular authorities throughout Europe conducted a concerted effort to prosecute those people deemed to be practicing witchcraft (see Faerie Familiars and Zoomorphic Witches). This persecution generated much artwork devoted to portraying events such as the witches’ sabbath and the various zoomorphic attributes of both the witches and their faerie familiars. Whilst much of this activity appears to have been metaphysical in nature, artists were not shy of outing the underground cult, often delighting in the more macabre details for the purposes of tabloidesque outrage amongst good Christians.

However, despite usually (but not always) being portrayed alongside witches and/or the Devil, the faeries begin to reassert their own artistic space during this period. Alongside the more benign reimagining of faeries in plays such as Shakespeare’s A Midsummer Night’s Dream, the faeries of literature – and the artistic visuals that accompanied this literature – begin to appear as autonomous entities, partially removed from demonic connotations. This is nicely illustrated by the 1639 cover to Robin Goodfellow His Mad Prankes and Merry Jests, which matches the japery of the text by portraying a distinctly mellow-looking Devil (complete with comedy codpiece) conducting a faerie circle dance.

This rehabilitation of the faeries began to bring them back into line with their folkloric roots, as supernatural entities with ambiguous morals but a more playful relationship with humanity and consensus reality. However, when we reach the 19th century, the art of faerie becomes transformed, and they become something else altogether.

The 19th-Century Reinvention of the faeries

In fact, the faerie artistic renaissance was underway by the later 18th century, inspired in part by the esoteric artwork of William Blake, who turned Shakespeare’s faeries into “the rulers of the vegetable world.” Blake’s style represented an innovative new representation of the faeries, and is perhaps the earliest (post-Antiquity) artistic rendering of them as sexual beings with an explicit connection to the fertility of the earth.

However, it took another generation of British Victorian artists to bring about the full-blown faerie revival. In her 1999 book Strange and Secret Peoples, Carole Silver details the socio-cultural reasons for this burgeoned interest in extracting the faeries from their shadowy past and putting them in the artistic spotlight:

“That the Victorians were utterly fascinated by the fairies is demonstrated by the art, drama, and literature they created and admired. Their abiding interest shows in the numerous, uniquely British fairy paintings that flourished between the 1830s and the 1870s – pictures in part inspired by nationalism and Shakespeare, in part as protest against the strictly useful and material, but in either case, as attempts to reconnect the actual and the occult.”

The revivalists were firmly rooted in the Romantic tradition, and whilst continuing Blake’s naturalistic visions of the faeries, they began to introduce new elements into their portrayals, not necessarily based on any folk traditions. For the first time the faeries attained wings, associating them with insects (especially butterflies and dragonflies), and many appeared as children, perhaps to accentuate their role as innocents amidst nature. There is a long list of Victorian British artists who jumped on the faerie bandwagon: John Anster Fitzgerald, Thomas Heatherley, Richard Dadd, John Duncan, Sir Joseph Noel Paton, John Atkinson Grimshaw, Richard Doyle (uncle of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle) to name just a few. All added their unique slant on things, but there was a consistency in their enchanted imagination, and they were responsible for cementing the idea of what faeries really were in the popular cultural imagination.

In the second half of the 19th century, just as the main phase of the revival was waning, there was a shift to a new style of faerie art. Artists such as Gustave Doré and Aubrey Beardsley began to plug into the Arthurian mythos revival, being made popular in literature at this time by Alfred Tennyson, Matthew Arnold, Algernon Charles Swinburne et al. There were plenty of faeries to capture from the legends, and Doré and Beardsley both created their own highly stylised imagery that added a new dimension to faerie art, which locked them into a mythic past, distinctly removed from the Victorian present.

Entering the mythic past was also the remit of the pre-Raphaelite school of painters, although in his concise article ‘Pre-Raphaelite Fairy Painting‘, Richard Schindler suggests they had a consistently more ambiguous relationship with faerie subjects than their more conventional artistic contemporaries. The folkloric qualities were almost entirely removed from this school of painting, making way for darkly sexualised imagery and the celebration of minute detail. In some ways the pre-Raphaelites almost took the faerie out of faerie art.

But at the end of the 19th century and into the early 20th century one artist in particular recaptured the folkloric realism in faerie art and produced a large and much-loved corpus of art that took the faeries back to their roots. Arthur Rackham was born in 1867 and began illustrating for books such as The Ingoldsby Legends and Fairy Tales of the Brothers Grimm in the 1890s. He continued to produce illustrations, mostly in ink and watercolour, for the rest of his life (he died in 1939), many of which portray the faeries from a vast range of folklore sources. His style is immediately recognisable and his copyright-free images can be found illustrating much modern online faerie content, suggesting his authoritative knowledge of traditional faerie-lore, and his ability to render it visually, has continued to strike a chord in the popular imagination. Of particular note are his illustrations for a 1933 edition of Christina Rossetti’s poem Goblin Market, where he fully realised the hallucinogenic earthy goblin faeries conjured up in this dark and sexually charged piece of literature. They look like emergent nature spirits, who don’t necessarily have the best interests of humans in mind, matching perfectly the ‘slightly dangerous’ faeries of folklore.

20th-Century Flower Faeries

During the early 20th century, however, there was another artistic movement afoot, which managed to derail any Rackhamesque faerie realism by transforming the faeries into characters for children. Taking the lead from some of the more gentle Victorian faerie artwork, artists such as Helen Jacobs and Margaret Rice Oxley turned the faeries into benign entities, fit for children’s faerie-tale book illustrations. The most influential artist of this time was Cicely Mary Barker, whose 1923 publication Flower Fairies, cast the faeries as innocent diminutive children, with each faerie allocated to a type of flower with an associated poem. Ironically, Barker’s illustrations were partly informed by the recent popularity of the Theosophical Society, and its ideas about the faeries as elemental beings essential for the wellbeing of nature and who were contactable through the altered state of consciousness most often known as clairvoyance. But any such metaphysical components were extracted from Barker’s illustrations, and we are left with the charming whimsy of the flower faeries.

It was Barker’s reimagining of the faeries that eventually morphed into the cinematographic faeries unleashed by Disney, and which continue to inform popular ideas about what they are: harmless, benevolent creatures, which exist to teach children morals and to delight us with their twinkly cuteness. Fortunately, on the back of the artistic counter-cultural renaissance of the 1960s, the faeries were rescued from expulsion into children’s books and films by the dynamic imagination of two artists who had rediscovered the folklore connection, and were willing and able to remind us what the faeries were really all about.

Froud and Lee Faeries

In 1978 Brian Froud and Alan Lee published the illustrated book Faeries, basing their descriptions and artwork on the folklorist Katherine Briggs’ An Encyclopaedia of Fairies, which had been published two years earlier. It has since been republished many times, and is without a doubt, the bestselling book about faeries. In the preface to the 2002 edition Brian Froud describes some of his thinking whilst putting together the original version:

In 1978 Brian Froud and Alan Lee published the illustrated book Faeries, basing their descriptions and artwork on the folklorist Katherine Briggs’ An Encyclopaedia of Fairies, which had been published two years earlier. It has since been republished many times, and is without a doubt, the bestselling book about faeries. In the preface to the 2002 edition Brian Froud describes some of his thinking whilst putting together the original version:

“Faeries is a reminder of a world in which we all once lived, where we were connected to the earth itself and could acknowledge its spiritual manifestations. There we recognised the souls of trees and rocks and rivers and had a direct relationship with the faeries – and to do otherwise was to court disaster. Faeries needed to be properly propitiated or else loss would be experienced – loss of objects, loss of time, loss of health, and even loss of life…

There is an intimacy of emotion expressed in the colour washes and a directness of meaning in the pencil and pen lines that delineate the faery forms.”

Faeries does indeed take us back to a naturalistic conception of what these entities are, but it’s also strongly rooted in the centuries old traditions of named and recognised faerie types, giving an encyclopaedic run through the varieties of these metaphysical creatures who have existed beside humanity, but always at the periphery of reality. Their faerie renderings are sometimes beautiful, sometimes frightening, and often amusing. But they plug into a deep understanding of a supernatural species that is intimately connected with human consciousness and the way it interacts with the natural environment, perhaps helping us to see that consciousness and external reality are one and the same thing. Froud and Lee’s illustrations have certainly had a far-reaching influence on subsequent artists of faeries as well as filmmakers – Froud has collaborated with Jim Henson, and Lee was drafted in by Peter Jackson to help recreate the creatures, atmosphere, artefacts and architecture of the Lord of the Rings trilogy. And modern imaginers of faerie worlds seem to intuitively incorporate many of their stylisms into their art. Perhaps this is because Froud and Lee have gotten closer than any other artists to the reality of the faerie world – they’ve pinned it down for what it really is… or at least as close as we can get to it.

The New Faeries

Froud and Lee’s faeries were primarily taken from British and Irish sources. In the 1992 book The Complete Encyclopaedia of Elves, Goblins and Other Little Creatures by Pierre Dubois, the artists Claudine and Roland Sabatier, evidently inspired by the artwork in Faeries, produced a compendious selection of global faeries. It’s a beautifully playful book that covers faerie traditions from every part of the world, once again claiming back the more sinister and uncomfortable aspects of the faeries. Before the advent of the internet this was the go-to book if you wanted a visual introduction to the faeries outside of Britain and Ireland, and it remains (alongside Faeries) a benchmark for contemporary artists who want to attempt bringing these entities into visual range.

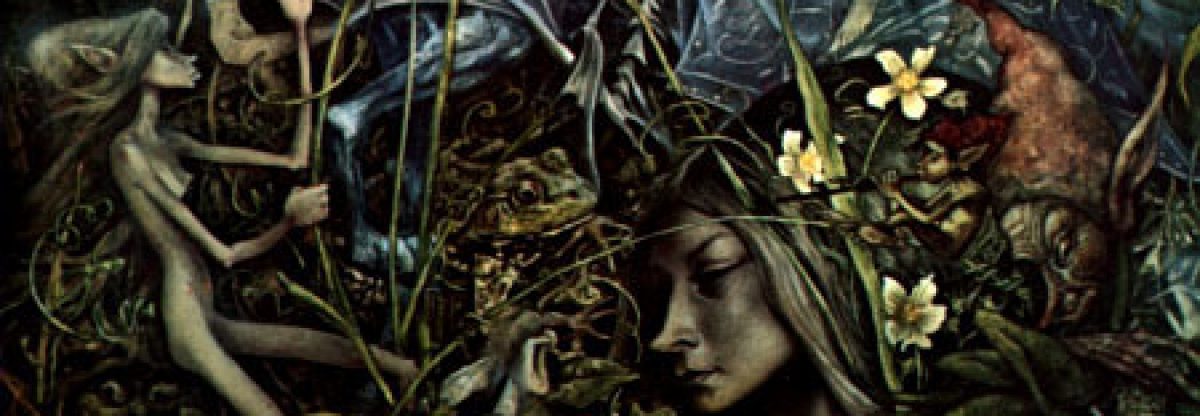

But it is the internet that has facilitated an exponential growth in new faerie art. Type ‘faeries’ into any image search engine and you will be deluged by a massive range of artwork, of every imaginable style, that depicts them as a distinct species of entity. A lot of it will be specifically for children, and often follows in the Flower Fairies tradition, but there is an enormous amount of innovative and charismatic faerie art being produced that looks at the phenomenon from a very wide spectrum. Artists such as Amelia Royce Leonards, Mia Araujo, Josephine Wall, Virginia Lee and Iris Compiet are helping us to see into the luminous, yet shadowy faerie-world in new ways; always respecting the artwork of the past but also bringing their unique visions to the table. It is a form of disclosure; the faeries being made manifest from the consciousness of talented artists who are able to tap into the metaphysical realm where they exist.

Finally, this post wouldn’t be complete without some visionary art by someone who has definitely met otherworldy beings in an altered state of consciousness with the aid of a psychedelic compound, in this case the Amazonian brew Ayahuasca. Pablo Amaringo was a Peruvian shaman (d. 2009) whose talent for illustrating his Ayahuasca experiences is unsurpassed. As Graham Hancock has eloquently described, Ayahuasca takes the human mind to radically different alternate realities, where reside many entities that correspond with faerie types. They exist – we just need to be able to tweak our everyday consciousness in order to interact with them. Fortunately, there have been many artists throughout prehistory and history who have been able to show us who they are and what they are.

The cover image is ‘Forest Healer’ by Mia Araujo http://art-by-mia.com

There are several hundred faerie images collected at Melissa Green’s Pinterest page here.

You might also enjoy the historic and contemporary images on my Facebook page The Faerie Code.

Loved this, thanks for writing!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks Alex…

LikeLiked by 1 person

Really great, and comprehensive look at Faerie art! Thanks for this.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Christine – much appreciated…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome! I enjoy your thoughtful examinations of the Fae world 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Neil, you have given me great pleasure and actually introduced some new artists to me here. I’ve been a follower of Faerie since early childhood, when my mum read me Noddy books and Little Grey Rabbit. I shared this article on FB and am now following your page, and I want you to know how thankful I am for your efforts. I am an artist, too, and I have been drawing and collecting fairy art and literature for my entire life. Visit my art on Facebook at my page, GrimalkinArt.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Victoria – just been looking at your fabulous artwork… great stuff… keep propitiating those faerie folk…

LikeLike

Neil- thanks for this. I enjoyed the world historical survey and you also mentioned some artists I hadn’t previously come across. I think pictures and illustrations are another really useful document of our evolving perceptions of faery nature- and not just nice decoration to our postings (although they are that too).

The link to Victorian web was also helpful; Schindler had some interesting observations, although I have to say that I thought he grossly overrated the influence of Blake and Dadd. No-one saw Dadd’s pictures after he entered Bedlam whilst, as we all know, Blake sold almost nothing during his lifetime, so that their paintings can only really be treated as evidence of their personal vision, not of any trends in art history. On that subject, handy as the online link is, I think that the two books by Christopher Wood and Jeremy Maas are far superior to Schindler in terms of putting fairy painting in a social context. His critique is largely artistic and subjective; the cultural, economic and social background are what really interest me.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for reading and the observations. I think Blake’s influence was great, although, as you say, post-mortem and not during his lifetime. I think this post probably needs a follow up that concentrates on contemporary faerie art, as I’ve discovered a lot of very good stuff since writing this piece. Some artists seem to be genuinely plugging into the metaphysical aspects of the phenomenon in a way that hasn’t been achieved before. Thanks again…

LikeLike

Fascinating ideas – keep posting

LikeLiked by 1 person