The medieval Welsh stories contained in what has become known as The Mabinogion hold many faerie motifs, and certainly resonate a magical folkloric ambience. This is an introductory overview of some of the stories from the collection. It only scratches the surface, but the references suggest some possibilities for further study into these preternatural tales. A version of this article first appeared on the Ancient Origins Premium website.

“On the bank of the river he saw a tall tree: from roots to crown one half was aflame and the other was green with leaves.” The History of Peredur Son of Evrawg.

The Mabinogion

The Mabinogion is a collection of eleven stories from medieval Wales. Although only first committed to manuscript during the 13th century (the oldest surviving fragmentary manuscript dates to c.1225), the tales are generally accepted as fossilising an oral tradition that dates back many centuries previous to this. They contain a heady mix of history, pseudo-history, mythology and folklore, and provide our most direct route into the Celtic mindset and worldview of ancient Welsh culture. The stories of The Mabinogion appear in complete form in two 14th-century Welsh manuscripts, ‘The White Book of Rhydderch’ (Llyfr Gwyn Rhydderch), and ‘The Red Book of Hergest’ (Llyfr Goch Hergest). They were all, originally, separate stories, written by different (unknown) hands, and were only collated into an autonomous group in the 19th century (first published as a complete set in 1849) by Lady Charlotte Guest, who translated the Welsh texts into English, using in part the earlier work of the Welsh antiquarian William Owen Pughe (d.1835). The eleven stories are usually split into the ‘four branches’:

Pwyll, Prince of Dyfed (Pwyll Pendefig Dyfed)

Branwen, daughter of Llŷr (Branwen ferch Llŷr)

Manawydan, son of Llŷr (Manawydan fab Llŷr)

Math, son of Mathonwy (Math fab Mathonwy)

and three ‘romances’:

The Lady of the Fountain (Chwedl Iarlles Ffynawn)

The History of Peredur son of Evrawg (Historia Peredur ab Efrawg)

Gereint and Enid (Geraint ac Enid)

and supplemented by four further stories of various dates:

Culhwch and Olwen (Culhwch ac Olwen)

The Dream of Macsen Wledig (Breuddwyd Macsen Wledig)

Lludd and Llefelys (Lludd a Llefelys)

The Dream of Rhonabwy (Breuddwyd Rhonabwy)

The quote from ‘Peredur’, describing the tree half aflame and half alive, illustrates well the preternatural quality that resonates through all the stories, where a magical Otherworld imbricates itself consistently into the landscapes of early medieval Wales. For those telling, listening to and reading the stories, this metaphysical overlapping would have represented a legitimate way of describing a past, where mythology and folklore were as authentic realities as the historical narrative. The characters, and their environment, were in physical reality and the Otherworld at the same time with no contradiction.

An Oral Tradition

Although the scenes and settings in The Mabinogion would have been immediately recognisable to people in the 13th and 14th centuries, when they became codified in manuscript form, the stories are nominally located in a post-Roman Wales, sometimes known as the Dark Ages. While it is not possible to trace the route sources of the stories, It seems certain that they developed from an oral tradition, a body of recitation lore, which has been given the Welsh name cyfarwyddyd (cer-var-with-id). The Mabinogion scholar Will Parker sums up the nature of this dissemination: “In pre-modern societies such as these, the oral tradition is the medium of collective memory; fluid in its details, but essentially static and conservative in its overall ethos… and we might assume that much of this material was informed, directly or otherwise, by the ambient oral tradition.”

Current academic opinion suggests that at least some of the stories in The Mabinogion can be dated back to the early 11th century, based on the structure and style of the narrative units, known by the medieval authors as chwedlau. But many of the themes contained within the stories are replete with pre-Christian imagery and tropes, and it is conceivable that they are transmitting much older traditions, originating from the 5th and 6th centuries. Although the stories would have evolved and mutated over such a long period of time, they do appear to represent a mythologised set of narratives, which could have been recited by storytellers at the courts of Dark Age chieftains just as well as within those of the later medieval Welsh aristocracy. But whatever the true origination of the lore, the subject matter portrays the real world of ancient Wales consistently energised and influenced by an Otherworld that was fully integrated into the consensus reality of both the storytellers and those consuming the stories.

The Arthurian Connection

One of the most intriguing aspects of The Mabinogion is that several of the stories connect to the Arthurian mythos. Without these stories, the earliest literary renditions of the activities of Arthur and his court are found in the works of Geoffrey of Monmouth, who, between 1135-1150, wrote the highly influential Historia Regum Britannia and Vita Merlini. Geoffrey appears to have utilised much oral folklore in his works, but there is a minimum of overlap with The Mabinogion tales, suggesting that he was using different branches of oral (and perhaps lost written) testimonies. The Mabinogion stories do transmit as more ‘folkloric’, with a heavier Celtic footprint and more reliant on folk motifs, which might insinuate they are the older corpus of material. Apart from some of the names, the Arthurian elements in the stories certainly bear little resemblance to what became ‘The Matter of Britain’; the recognisable story of King Arthur, begun by Geoffrey of Monmouth and then propagated by continental authors such as Chrétien de Troyes and Wolfram von Eschenbach, before ending up in the hands of Sir Thomas Malory in the late 15th century. For all the supernatural components included in this later literature, they are not as embedded with the surreal as the stories in The Mabinogion.

In the story of ‘Culhwch and Olwen’ (often seen as the earliest of the tales) the role of Arthur’s court is paramount. But the king’s men, who are requisitioned to help Culhwch in his quest to obtain the hand of Olwen from her father (the giant Ysbaddaden Bencawr) are evidently drawn from otherworldly stock and are given supernatural attributes, such as Sgilti Yscawndroed, who is able to transport himself great distances by treading over the tops of trees and even flying over mountains by utilising the tips of reeds. This was a skill shared with the Tylwyth Teg, the folkloric faeries of Wales. The giant father demands that forty tasks are achieved before he allows Culhwch to marry Olwen, a common folktale motif, and the story proceeds to recount a small number of these tasks, all of which have fantastical qualities. The task of hunting the magical boar Twrch Trwyth takes up the most prose, and seems to be partly based on the 9th-century Irish legends of Diarmuid Ua Duibhne. But the deeper Arthurian connection is made in the task of retrieving the cauldron of Diwrnach. This cauldron can be equated with the grail of the later Arthurian mythos, and its alchemical significance is confirmed by the firepower Arthur and his men implement in its retrieval. The grail motif is made more explicit in ‘The History of Peredur son of Evrawg,’ where the hero Peredur, after being dispatched to his uncle’s castle by Arthur, is confronted by a procession lead by an entity carrying a salver with a severed head. As usual in The Mabinogion, the significance of this is left ambiguous, but the motif of a magical salver/grail seems to have seeped into later renditions of the Arthurian mythos, where it was given more prominence, until (in the early 13th century) Robert de Boron classified it as the cup in which Joseph of Arimathea caught the blood of Christ on the cross.

There is some contention as to how much cross-pollination there has been from The Mabinogion Arthurian stories to the later ‘Matter of Britain’, and even whether the Welsh manuscript sources were reintegrating French and German literature from the 12th and 13th centuries. But even if they were capturing motifs from these continental sources, the Welsh stories retain decisive elements of a magico-folkloric quality that appear to come from a pure stream of Celtic mysticism. This is best demonstrated in what is usually thought to be the latest of the stories, but the one that includes the most magical symbolism, hinting at an early source to its metaphysical prose. This is ‘The Dream of Rhonabwy.’

Magico-Folklore in Medieval Wales – ‘The Dream of Rhonabwy’

Although the beginning of the story is set in the mid-12th century, with known historical personages from the kingdom of Powys, the main bulk of the prose consists of Rhonabwy’s dream, which takes him into a magical Otherworld that interfaces with a Dark Age, Arthurian pseudo-history. The first clue that the writer of the story is tapping into some ancient belief-systems comes as Rhonabwy finds himself in the squalid, dilapidated home of ‘Heilyn Goch son of Cadwgan son of Iddon.’ Rhonabwy sleeps wrapped in a yellow ox-hide situated on the dais of the hall. Sleeping in an ox-hide in order to gain oracular insights is attested to in Inuit and Siberian shamanic cultures from the 19th and 20th centuries, and is also portrayed in pre-Christian Irish texts such as Togail Bruidne Dá Derga. Such an episode even finds its way into Geoffrey of Monmouth’s Historia Regum Brittaniae. Listeners to (and readers of) the story may not have been aware of the significance of Rhonabwy’s action, but it is clearly a symbolic deed that indicates the story is about to enter the metaphysical.

Rhonabwy’s dream has the hallmarks of an out of body experience, where he is mostly a discarnate observer of events, consistently described as a vision: “As soon as sleep entered his eyes he was granted a vision.” This is enabled by his (spirit) guide Iddawg who discloses that it was he who was responsible for the disastrous last battle of King Arthur (termed emperor throughout the story) at Camlann. But, after the appearance of a horseman “with curly yellow hair and his beard newly trimmed, on a yellow horse, and from the top of its forelegs and its kneecaps downwards green,” the dream then immediately transposes back in time as Rhonabwy is taken by his guide across a plain to witness the prequel to the Battle of Badon, the scene of Arthur’s first and greatest victory of the Saxon armies at some point in the early 6th century. When they come upon Arthur, Iddwag tells Rhonabwy that by seeing the stone set within a ring on Arthur’s finger “you will remember all that you have seen here tonight; had you not seen the stone you would have remembered nothing.” The stone may be seen as a magic talisman, serving as the link between physical reality and the Otherworld, another common shamanic trope and folkloric motif.

In his visionary state, Rhonabwy witnesses a series of surreal events, centred around a game of gwyddbwyll (a chess-like board game) between Arthur and his retainer Owain mab Urien. At one point the players are asked to intervene as a flock of ravens dismember a number of their men (dismemberment in the Otherworld is another shamanic device, meant as a sign of spiritual renewal before return to physical reality), before the enigmatic arrival of twenty-four donkeys with baskets of gold and silver, which were to be given to Arthur’s bards. The story ends before any battle takes place, and the purpose and meaning is left undisclosed, as Rhonabwy awakes on the ox-hide having slept for three days and three nights.

Much of the otherworldy symbolism in ‘The Dream of Rhonobwy’ remains undecipherable, and it seems probable that even the late-medieval purveyors of the story were not fully aware of the pre-Christian and shamanistic elements contained in the narrative. But like all the stories in The Mabinogion, it was transmitting an ancient set of folkloric and mythological motifs that relied on an Otherworld to give meaning to the historic past of Wales. In this sense, the stories retain an embedded function and purpose that transcends their historical context, and continue to enhance our understanding of the ontological inheritance of metaphysical belief-systems so fundamental to the Celtic (and especially Welsh) cultural mindset.

References

Ashe, Geoffrey. The Origins of the Arthurian Legends (1995) http://faculty.smu.edu/bwheeler/arthur/ashe.pdf

Davies, Sioned (tr.), The Mabinogion (2007).

Green, Thomas. Concepts of Arthur (2008).

Guest, Lady Charlotte (tr.), The Mabinogion (1877 ed.) http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/celt/mab/index.htm

Historia Regum Britannia by Geoffrey of Monmouth http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/gem/index.htm

Lacy, Norris, J. et al. The New Arthurian Encyclopedia (1996).

Parker, Will. http://www.mabinogion.info (2010). This site contains an in-depth discussion and interpretation of The Mabinogion, with links to the full translated texts with notes.

Vita Merlini by Geoffrey of Monmouth http://www.sacred-texts.com/neu/eng/vm/index.htm

Wilson, Anne. The Magical Quest: The Use of Magic in Arthurian Romance (1988).

Wilson, Anne. Plots and Powers: Magical Structures in Medieval Narrative (2001).

A round-table discussion about The Mabinogion on the BBC series ‘In Our Time’ can be streamed or downloaded here: https://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/b0b1p5k7#play

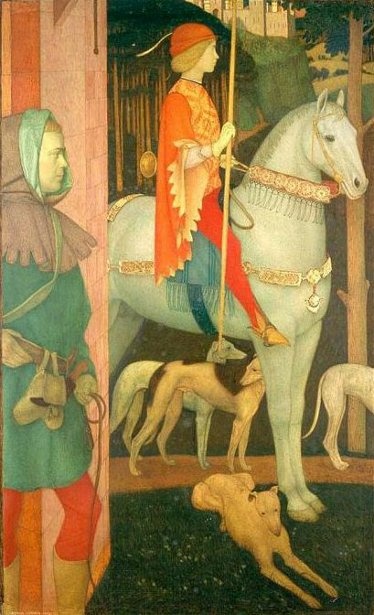

The cover image is ‘Culhwch’ by Arthur Joseph Gaskin (1921).

Reblogged this on Lilaia Moreli – Words Are Sacred.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Many thanks Lilaia, this is appreciated…

LikeLiked by 1 person

You’re welcome. Thanks for sharing this. I’m a huge lover of Celtic culture and tradition. The ”Mabinogion” is a book very close to my heart. I will return to it many times in the future.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Another wonderful article, which I devoured with joy. Now I am compelled to read again five books I’ve been toting between moves beginning in 1974: The Maginogi and other Medieval Welsh Tales, translated & edited by Patrick K. Ford (1977 University of California Press); Prince of Annwn, The Children of Llyr, The Song of Rhiannon, and The Island of the Mighty, all by Evangeline Walton. Thank you for continued inspiration.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for your kind words Victoria. The story cycle is certainly worth many revisits. The illustrated version of Charlotte Guest’s translation by Alan Lee is also very inspirational…

LikeLike

A very well-written and interesting piece! Great work!

LikeLiked by 1 person