This is a companion piece to an article for the Ancient Origins Premium website.

In her 2005 book Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits, and the 2010 follow-up The Visions of Isobel Gowdie, Emma Wilby consolidates, and expands upon, a couple of decades of work by, mostly, continental scholars who had been investigating the possibility that records of medieval and Early Modern witch trials were documenting the survival of a pre-Christian shamanic visionary tradition. Until that point, study of the relatively large numbers of recorded witch trials in Britain had concentrated on the mechanisms of persecution, rather than any examination of the actual beliefs of the persecuted. Indeed, heavy-weight historians such as Hugh Trevor-Roper insisted that the only legitimate interpretation of the evidence from witch trials was as a function of social and cultural attitudes towards an aberrant cult. The voices of the persecuted were conveyed to us exclusively through the lens of the secular and clerical judiciary, and, according to  Trevor-Roper and other historians, it was only the attitudes of these cultural elites that could be discerned from the documentation. The actual recorded beliefs of the accused witches were simply ‘disturbances of a psychotic nature’, ‘fantasies of mountain peasants’, and ‘mental rubbish of peasant credulity and feminine hysteria.’ In other words, any suggestion that the phenomenon the accused witches were recorded as describing might have elements of truth to it was baloney. But Wilby, following the lead of Carlo Ginzburg, suggests that if we attempt to excavate the actual words and beliefs of the persecuted witches, we discover that they were describing a remnant of pre-Christian shamanism, alive and well and, until the Inquisition caught up with them, operating under the radar of the Church.

Trevor-Roper and other historians, it was only the attitudes of these cultural elites that could be discerned from the documentation. The actual recorded beliefs of the accused witches were simply ‘disturbances of a psychotic nature’, ‘fantasies of mountain peasants’, and ‘mental rubbish of peasant credulity and feminine hysteria.’ In other words, any suggestion that the phenomenon the accused witches were recorded as describing might have elements of truth to it was baloney. But Wilby, following the lead of Carlo Ginzburg, suggests that if we attempt to excavate the actual words and beliefs of the persecuted witches, we discover that they were describing a remnant of pre-Christian shamanism, alive and well and, until the Inquisition caught up with them, operating under the radar of the Church.

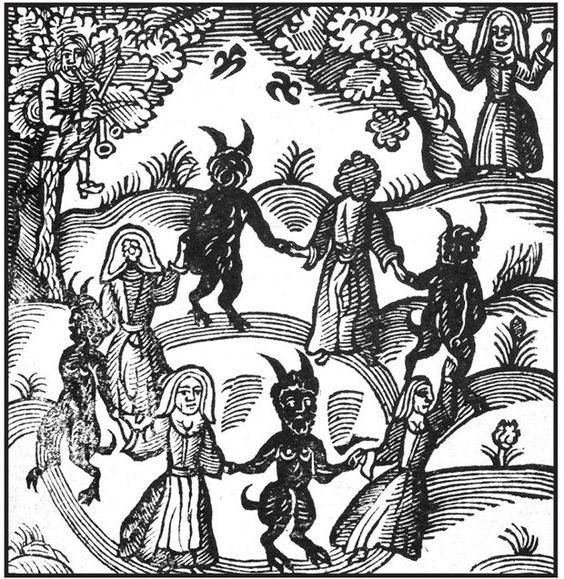

The Witches’ Sabbath

Two of the most important elements of the records from the witch trials were the descriptions of witches’ faerie familiars and the supposed zoomorphic ability of witches to shape-shift into animals for various purposes. The records are replete with descriptions of faerie familiars, which could appear to, and interact with witches as humanoid faeries or as animals of various sorts, and depictions of witches transforming themselves into a diverse range of creatures for disparate objectives.

On the continent, faerie familiars and zoomorphism were usually described as agents of travel, most often to the witches’ sabbath. Ginzburg summarises the basic features of the sabbath that recur in many of the witch trial documents:

‘Male and female witches met at night, generally in solitary places, in fields or on mountains. Sometimes, having anointed their bodies, they flew, arriving astride poles or broomsticks; sometimes they arrived on the back of animals, or transformed into animals themselves. Those who are for the first time had to renounce the Christian faith, desecrate the sacrament and offer homage to the devil, who was present in human or (most often) animal or semi-animal form. There would follow banquets, dancing, sexual orgies. Before returning home the female and male witches received evil ointments made from children’s fat and other ingredients.’

These components, as recorded by the persecutors of the witches, persist as central themes in witch trials through the later Middle Ages in Europe and, in some places, until the 18th century. Tens of thousands of people (men and women) were burnt at the stake for witchcraft during this period.

As early as the 12th century (pre-Inquisition) a document known as the Canon Episcopi warned its readers that: ‘… some wicked women believe and profess themselves, in the hours of night, to ride upon certain beasts, which they keep for the purpose. They ride with [the pagan goddess] Diana and an innumerable multitude of women, and in the silence of the dead of night, they traverse great spaces of earth.’ There were various animals that could fit the bill as familiars, they could be mice, cats, dogs, birds, insects, horses, bears, foxes, frogs, even hedgehogs, though the most popular were goats – witches riding astride goats were commonly portrayed in medieval and Early Modern illustrations, and even in architectural reliefs, such as at Lyons Cathedral, where a witch is shown riding a goat and holding a hare (shown above).

animals that could fit the bill as familiars, they could be mice, cats, dogs, birds, insects, horses, bears, foxes, frogs, even hedgehogs, though the most popular were goats – witches riding astride goats were commonly portrayed in medieval and Early Modern illustrations, and even in architectural reliefs, such as at Lyons Cathedral, where a witch is shown riding a goat and holding a hare (shown above).

Amongst the best recorded of European witch cults were the Benandanti in north-east Italy during the 16th and 17th centuries. They seem to have utilised animal familiars as well as being able to shape-shift into a variety of creatures themselves, to attend sabbaths, visit faerieland and to do night battles with what they perceived as ‘evil witches’ who were using their own shape-shifting abilities to blight crops and cause illness on targeted individuals. Carlo Ginzburg’s 1966 study The Night Battles, details the complex belief systems of the Benandanti, who were rooted out by the Inquisition over a long period of time. Their trials provide some of the most comprehensive evidence for the ontology of the witches’ sabbath and travels to a faerieland in Early Modern Europe, which their inquisitors insisted to be the work of the Devil.

Members of the Benandanti could also travel to the Otherworld with humanoid faerie familiars. At a witch trial in 1591, one of the accused, Menichino della Nota, confessed that he would travel to Josaphat’s Field (one of the Benandanti’s names for the Otherworld) through the auspices of a faerie lady known as ‘the abbess’. Three decades later (and as usual, under torture), another Benandanti, Maria Canzona, also talked of ‘the abbess’, who she seemed to equate with the Queen of the Faeries. ‘The abbess’ would meet with Maria outside of her village and then they would fly to their destinations together. Other European witches of the period also usually equated humanoid faerie familiars as female. In 16th-century Sicily, in a series of witch trials, all of the female witches confessed to meeting with ‘Night Women’ or ‘The Ladies from Outside’, with who they would fly to far distant meadows to dance and feast at ceremonies presided over by the ‘Wise Sibilla’, another name for the faerie queen. Interestingly, the ‘Night Women’ were described as beautiful, but as having cats’ paws or horses’ hooves.

Zoomorphism

The zoomorphic quality of witches, to change themselves into metaphysical animal forms, is well attested in European witch trials. The concept has a very long history. In the 2nd century the Platonist philosopher Apuleius, in his extended poem Metamorphoses, described the shape-shifting abilities of female witches in the region of Thessaly, Greece: ‘These atrocious chameleons transform themselves into any kind of animal whatsoever. They disguise themselves as birds, dogs, weasels, mice and even flies.’ Apuleius does not go into detail as to what these women were doing during their zoomorphic state. But by the time of the witch persecutions from the 15th century onwards, the records have much more to say about this. In his 1998 book Witches and the Shamanic Journey, Kenneth Johnson extracts material from the late medieval witch trials from central and northern Europe, where the accused frequently described their transformations into a wide variety of animals:

“… shape-shifting appears as an integral part of the witch trials almost from the very beginning. In the Valais trials, part of the first wave of persecutions, which date from the early 1400s and were centred in the Western Alps, the male witches said that they took the shape of wolves, and that ‘the Devil’ appeared to his devotees in the

shape of a bear or a ram. A half century later, a German demonological text by Ulrich Molitor includes an illustration (below) showing witches on the way to the Sabbath, midway through their transformations into animals.”

Johnson also quotes a 1540 text by Hermann Witekind from Livonia (now Lithuania, and the last part of Europe to be officially converted to Christianity in 1386), who interviewed a male peasant who was awaiting his trial after being imprisoned for witchcraft. Witekind (incredulously) reports that the peasant was dancing around his cell, joyously informing him that the previous night he had been able to escape his captivity by transforming himself into a wolf and bounding across the landscape to ‘an immense river.’ He only returned to the cell ‘because his master wished it.’

British Witches and the Faeries

In Britain, the full-blown witch hunts seen in Europe were resisted until a later date. But  by the late 16th century this was being rectified, and even King James VI of Scotland (later James I of a united kingdom with England) himself felt compelled to write Daemonologie (first published in 1597), which acted as a condemnation of the heresies of necromancy and witchcraft, evidently penned with much personal knowledge of the phenomena. Through the 17th century, both the Church and secular authorities made up for lost time, and thousands of witches were prosecuted in England, Wales and Scotland, many of them being burnt, drowned or hung if found guilty. Emma Wilby’s penetrative analyses of the witch trial records from this time finds (as with the records from the continent) much evidence for the hypothesis that the accused witches were practicing an adapted form of pre-Christian shamanism, where faerie familiars and zoomorphism played an essential and consistent role in the tradition they were following.

by the late 16th century this was being rectified, and even King James VI of Scotland (later James I of a united kingdom with England) himself felt compelled to write Daemonologie (first published in 1597), which acted as a condemnation of the heresies of necromancy and witchcraft, evidently penned with much personal knowledge of the phenomena. Through the 17th century, both the Church and secular authorities made up for lost time, and thousands of witches were prosecuted in England, Wales and Scotland, many of them being burnt, drowned or hung if found guilty. Emma Wilby’s penetrative analyses of the witch trial records from this time finds (as with the records from the continent) much evidence for the hypothesis that the accused witches were practicing an adapted form of pre-Christian shamanism, where faerie familiars and zoomorphism played an essential and consistent role in the tradition they were following.

During a compendious outpouring of confessions during her trial for witchcraft in Scotland in 1662, Isobel Gowdie (for once, without torture, and fully backed-up by her co-accused) told her interrogators that after anointing herself with certain ‘unctions’ she shape-shifted into a hare before flying to the Sabbath. She also chanted an incantation to ensure the transformation:

I shall go into a hare,

With sorrow, sigh, and mickle care;

And I shall go in the Devil’s name,

Aye while I come back again.

Isobel and her fellow accused witches also confessed to combining the use of faerie familiars with zoomorphism to attain their goals, which were sometimes beneficent, and sometimes maleficent. Whatever the objectives of these Scottish witches, their testimonies confirm their belief that in order to interact with a faerie otherworld they were reliant on the aid of familiars, or on their ability to turn themselves into animals. Isobel Gowdie again:

Isobel and her fellow accused witches also confessed to combining the use of faerie familiars with zoomorphism to attain their goals, which were sometimes beneficent, and sometimes maleficent. Whatever the objectives of these Scottish witches, their testimonies confirm their belief that in order to interact with a faerie otherworld they were reliant on the aid of familiars, or on their ability to turn themselves into animals. Isobel Gowdie again:

‘I had a little horse, and would say: ‘Horse and hattock, in the Devil’s name!’ And then we would fly away, wherever we would, even as straws would fly upon a highway. And when we would be in the shape of crows, we would be larger than ordinary crows, and would sit upon the branches of trees. We went in the shape of rooks to Mr Donaldson’s house… and went in at the kitchen chimney…’

A decade later, and under more intimidatory cross-examination, the Northumberland witch Anne Armstrong claimed that she was commanded to sing whilst her companion witches: ‘danced in several shapes, first of a hare, then of their own, then in a cat, sometimes a mouse, and several other shapes.’

A decade later, and under more intimidatory cross-examination, the Northumberland witch Anne Armstrong claimed that she was commanded to sing whilst her companion witches: ‘danced in several shapes, first of a hare, then of their own, then in a cat, sometimes a mouse, and several other shapes.’

British faerie familiars took a wide variety of forms. In the trial of Bessie Dunlop in Edinburgh in 1576, she describes what might be seen as a traditional folkloric humanoid faerie, who went by the name of Tom Reid. She described him as a diminutive being who would appear to her only when she was alone. He was:

‘… an elderly man, grey bearded, and had a grey coat with Lombard sleeves of the old fashion, a pair of grey breeches and white stockings gartered above the knee, a black bonnet on his head… with silken laces drawn through the edges thereof, and a white wand in his hand.’

British witch trials, like their European counterparts, were conducted and recorded by the persecuting cultural elite, and much caution is required in taking confessions extorted under duress as evidence of the actual words of the accused. But the consistency, over long periods of time, in descriptions of faerie familiars and the perceived abilities of witches to transform themselves into animals, confirms that we are being handed down testimonies of a genuine visionary tradition. But it is a tradition with an overt metaphysical component. As the narrative from a Taunton witch trial in 1664 states: ‘The witches are carried sometimes in their bodies and clothes, at other times without, and the examiner thinks their bodies are sometimes left behind. Even when their spirits only are present, yet they know one another.’ The Christian prosecutors evidently did not know what to make of this apparent ability of witches to act metaphysically. It would invariably be recognised as the work of the Devil, but the examiners’ understanding of the confessions never involved the recognition of a deep-set visionary tradition being tapped into by the rural peasantry, that was outside of the Christian orthodox belief system.

Physical vs Metaphysical and the Shamanic Experience

Whilst medieval and Early Modern people who considered themselves (and were considered as) witches, did convene at ritual gatherings in physical reality, for a variety of purposes, the surviving documentation strongly suggests that they were also engaging in a metaphysical reality. Many of their inquisitors and contemporary commentators were incredulous at these testimonies of out of the body travel and animal shape-shifting, and would usually attempt to explain the experiences as the delusional work of the Devil. The Swiss preacher Johann Geiler von Kaiserberg summed up the general view in 1508:

‘What will you tell us about those who travel by night and assemble thus? When they travel to Venus Mountain, or when the witches travel here and there, do they travel, or do they stay, or is it an illusion? As to the first, I say that they do travel here and there but that their bodies remain in one place. They think that they travel, for the Devil can create that delusion in their head.’

What is described as happening to the people involved in witchcraft in these periods, bears many of the hallmarks of shamanistic practice. Shamanism is not an organised religion, it is rather a technique for direct contact with a metaphysical, spiritual reality through the arbitration of individuals able to reach that reality by altering their states of consciousness. This contact with a spiritual, non-physical realm was/is usually conducted to bring back information from that realm, that is deemed useful, such as healing,

What is described as happening to the people involved in witchcraft in these periods, bears many of the hallmarks of shamanistic practice. Shamanism is not an organised religion, it is rather a technique for direct contact with a metaphysical, spiritual reality through the arbitration of individuals able to reach that reality by altering their states of consciousness. This contact with a spiritual, non-physical realm was/is usually conducted to bring back information from that realm, that is deemed useful, such as healing,

premonitions of the future, and advice from ancestral spirits. In his groundbreaking 1951 book Shamanism: Archaic Techniques of Ecstasy, Mircea Eliade details the development of shamanism all over the world, coming to the conclusion that the ontological similarities in all forms of shamanism (which is, or was, widespread in every continent) must mean that it has a common prehistoric source datable to the Upper Palaeolithic. Recent work on Palaeolithic cave paintings convincingly demonstrates that many of the images represent shamanic altered states of consciousness, supporting Eliade’s ideas that the stratum of shamanism began at this period and diffused everywhere through time until replaced (or overlain) by formal religions. It was the original human spiritual belief.

Many of the core attributes of shamanism described by Eliade (and by many anthropologists since) find resonance in the practices of pre-modern witches. Through a variety of methods – including ingestion of psychotropic plants and mushrooms, fasting, dance, illness, sensory deprivation – the shaman falls into an ecstatic trance. His/her body is left in a cataleptic state, whilst their consciousness is removed elsewhere, always with the aid of a totem animal. The shaman’s consciousness either becomes the animal or is guided by an animal during their out of body experience, enabling them to travel to a variety of metaphysical realms and bring back the required, or sought information. During these ecstasies, the shaman is able to encounter other shamans (both friendly and hostile), who similarly disassociate their consciousness from their physical selves. These are the basic components of the witches’ ecstasies described through the medium of their Christian persecutors. Whether these visionary episodes were remnants of pre-Christian Eurasian shamanism, or whether they were diffused from marginal societies in parts of Scandinavia, Eastern Europe and Siberia, where shamanism survived (in various forms) throughout the period, remains equivocal. But the ontological correlations strongly suggest that there was a medieval and Early Modern heretical witch cult in many parts of Europe, existing beneath the prevailing Christian orthodoxy, which utilised aspects of shamanism as its modus operandi.

Unfortunately, inquisitors were rarely interested in the means employed by witches to alter their states of consciousness, and so we are left with ambiguous references to ‘salves’, ‘unctions’ and ‘potions’, used to attain ecstasies. Whilst there is a wealth of direct evidence for the techniques used by shamans around the world, and through time, to reach visionary states, the historic documents used to penetrate the witches’ sabbaths fall short of disclosure. But the documents, despite being so heavily overlain by the value judgements of Christianity, do consistently point to journeys to Sabbaths and faerieland being metaphysical events. Just as this was difficult to stomach for the Christian inquisitors of the witches, it also challenges our own materialistic worldview. But if we want to infiltrate the reality of the witches’ world, we are compelled to consider the shamanic cosmological viewpoint that consciousness is an autonomous non-physical reality, which can be manipulated to act independently and metaphysically for ritual and spiritual purposes. It was an adherence to this principle that cost the lives of so many medieval and Early Modern witches at the hands of their persecutors. They were shamans in all but name, and as such, were unacceptable within the strictures of orthodox Christianity.

Modern Wicca and the Shamanic Component

Modern Wicca seems to be divided on the shamanic component of witchcraft. But there is a growing recognition that the ritualised metaphysical component of witchcraft is fundamental to understanding the spirituality that is at the root of modern Wicca, whichever path is taken. Modern witches owe a lot to their medieval and Early Modern predecessors, who practiced their visionary traditions at risk to their own lives – something that modern witches do not have to worry about. Most especially, the concept of a faerie or animal familiar, and the need to engage in an altered state of consciousness to seek wisdom and healing, has found its way into the structures of modern witchcraft, and it’s usually based on the shamanistic visionary traditions of our ancestors. The excellent website at Witcheslore.com has a powerful piece on Familiars, which articulates the role of the faerie familiar and zoomorphism, and recognises the essential relationship with shamanism and its metaphysical underpinning. The final word is theirs, with an appreciation that the modern witch recognises what their spiritual ancestors would have known instinctively…

‘An altered state of consciousness or trance state, allows the witch to astral project, when this happens the witch’s consciousness leaves the physical body and is able to travel where and as they choose. As faeries live in a spirit realm, a witch often used a faerie as a familiar, this allowed the witch a doorway into the otherworld, witches and faeries were often connected and worked well together. Familiars are powerful healers and are messengers between one world and the other, they are wonderful and loyal companions for a witch. The three types of familiars are, the physical, the spirit and the artificial. The physical familiar is a pet, animal or creature; the spirit is a conscious entity that exists within the otherworld, beyond the land of the living. Magic also is used for the creation of an artificial familiar.’

The cover image is the frontispiece to Richard Bovet’s Pandaemonium, or the Devil’s Cloyster (1664).

Interesting stuff! They definitely practiced folkloric and pre Christian traditions. One wonders how much was confessed or ‘made up’ under torture — however, there are also many confessions that were freely given, and even some cases of telepathy. Thanks for posting!

LikeLiked by 1 person

Reblogged this on Kate McClelland and commented:

A long read but very interesting. Thank you for posting this

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Kate – much appreciated…

LikeLiked by 1 person

This article looks fascinating, but I will have to return to read (and share) it another day. Thanks for your wonderful work.

LikeLiked by 1 person

A very in-depth and well researched article. Most fascinating.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you – much appreciated…

LikeLike

Enjoyed this very much, especially since I just finished reading a novel, Shadow of Night, by Deborah E. Harkness, in which the main characters time travel back to 1590, during the witch trials in Scotland. Your lucid article made me feel right at home.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you so much – it’s appreciated. Glad you enjoyed…

LikeLike

Yes, we’ll done.

A few points. Apulia wrote The Golden Ass, not Metamorphoses.

Whole the identifiction of shamanic elements in witchcraft is fascinating, what seems to be glossed over is that these witches were, ahem, having sexual congress with demons. So the next step would be to identify traditions which connect the use of demons or malevolent spirits in order to undertake these soul-journeys. On a related note, are there reports of witches going on a soul-trip without the aid of demons?

LikeLiked by 1 person

‘Well done’ not we’ll

‘While’ not whole

Pardon the mistakes

LikeLike

Thank you for reading Coco. I understand that Apuleius’ work has interchangeable titles… I got the information from: S. Tilg (2014), ‘Apuleius’ Metamorphoses: A Study in Roman Fiction.’ The sexual congress issue is interesting. There are some good observations on this in Emma Wilby’s 2010 book ‘The Visions of Isobel Gowdie’ – maybe I’ll try to expand on this in a future article. My understanding is that, in most historical sources, the witches always travelled with a familiar of some sort, but this might be simply due to the nature of the sources. As always, more research may elucidate. Thanks again…

LikeLike

Incredible research here, Dr. Rushton. Thank you so much for the compelling information. Definitely inspires me to read further.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you Jennifer – much appreciated.

LikeLiked by 1 person