taboo [ta·boo | tə-‘bü] NOUN

A social or religious custom prohibiting or restricting a particular practice or forbidding association with a particular person, place, or thing.

Taboo motifs are common in both traditional faerie-tales and folklore. In traditional tales they can form the centrepiece of the plotline; the crux that everything turns on, usually marking a change in state from supernatural to natural or vice-versa. In more anecdotal folklore their function is also often central to the didactics of the testimony. Whether the action takes place in a faerie Otherworld with a human placed under the edicts of a taboo, or whether it is a faerie in consensus reality imposing unbreakable taboos on humans, the motif appears to represent a fundamental premise concerning the interaction between physical and metaphysical reality. It would seem the taboo is a coded message that may help unlock the meaning of the tales and folklore. But the code is usually deeply embedded and buried beneath metaphors and symbolism that often appear too layered and hidden to elicit any explanation as to the purpose of the taboos. They are most often surreal and even absurd parts of tales and folklore. So are these taboo motifs inserted into stories simply as useful plot devices and to invoke a sense of magical realism in folk tales, or do they have a more profound significance, locked into the transpersonal memory of folklore as hermeneutic tools to interpret aspects of reality and the human condition?

Taboos in Faerie-Tales and Folklore

Faerie-tale taboos come in many forms but in essence, they represent prohibitions invoked by faerie entities that cannot be broken. Invariably, they are broken and the consequences are as promised. These consequences are nearly always (though not exclusively) detrimental to the human protagonists of the stories. The motif is ancient and finds its way into several early-medieval Irish tales, the most well-known being Oisín in Tír na nÓg, which includes a double-taboo. Oisín is a poet of the Fianna, and falls asleep under an ash tree. He awakes to find Niamh, Queen of Tír na nÓg, the land of perpetual youth, inhabited by the Tuatha Dé Danann, summoning him to join her in her realm as husband. He agrees and for three years he finds himself living in a paradise of perpetual summer and where time and death hold no sway. Oisín and Niamh even have three children together. But soon he breaks the taboo of standing on a broad flat stone, from where he is able to view the Ireland he left behind. It has changed for the worse, and he begs Niamh to give him leave to return. She reluctantly agrees but asks that he return after only one day with the mortal inhabitants. She supplies him with a magical black horse, which he is not to dismount, and ‘gifted him with wisdom and knowledge far surpassing that of men.’ Once back in Ireland he realises that three hundred years have passed and that he is no longer recognised or known. Inevitably, he dismounts his horse and immediately his youth is gone and he becomes an enfeebled old man with nothing but his immortal wisdom. There is no returning to the faerieland of Tír na nÓg. In other variations of the story, the hero breaks the taboo and turns to dust as soon as his feet touch the ground of consensus reality.

Medieval prose and poetry from Britain and France also used the taboo motif frequently, usually within the Arthurian cycle of stories, which often involved a faerie Otherworld as an essential component of the mythos. Chrétien de Troyes’s romance Yvain, the Knight of the Lion, is the earliest text example (12th century), where Yvain (like Oisín) falls in love with the Otherworldly faerie, Laudine, and lives with her in a magical land. After a time, he leaves to return to his own world under her stipulation (the taboo) that he returns after a year and a day. He fails to do so and is therefore rejected by her and prohibited from re-entering the faerie Otherworld. In the 14th-century Middle-English romance Sir Launfal by Thomas Chestre (based on the 12th-century Lanval by Marie de France) Launfal is undone by uttering the name of his faerie lover Tryamour (a theme explored below), who had previously bestowed gifts on him – including a faerie horse, an invisible servant and a self-replenishing bag of gold coins – and promised to come to him whenever he wished, provided he adhered to the taboo of never naming her to another human. Once he has uttered her name (to Queen Guenevere no less) and broken the taboo, she comes to him no more and the gifts she has given him disappear.

This Arthurian mythos was plugging into earlier Celtic stories, which may have dated from at least the 8th century in written form and to the pre-Christian era in oral tradition. So the regurgitation of the taboo motif through the Middle Ages demonstrates a continuation of its Pagan metaphysical significance, even if the composers of the stories in the later medieval period were not fully aware of the coded meaning of the motif. They may have been using it as a useful magical plot device, but they were, in fact, perpetuating an ancient symbolic motif that was an intrinsic part of stories where a faerie Otherworld formed part of the narrative.

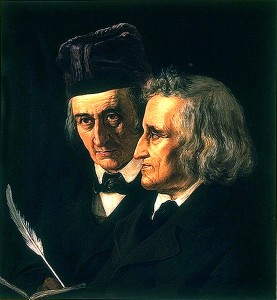

The taboo motif evidently continued to form part of evolving oral folklore in the post-medieval period until the stories began to be recorded in the 19th century. When Jakob and Wilhelm Grimm recorded their traditional European faerie-tales in the early 19th century about a third of them incorporated a taboo motif. The motifs found many forms but are all recognisable as magical prohibitions. In Cinderella, the midnight curfew is the prohibition invoked by the ‘fairy godmother’, which allows the heroine to maintain an aura of glamour to achieve her goals, but which has a defined time-period before the magic is taken away. When Cinderella breaks the curfew/taboo she has to quickly escape the constructed reality, losing her slipper as she does so, and thereby setting up the rest of the story. In Little Brother and Little Sister, a witch (a common propagator of taboos in faerie-tales) sets up the prohibition to the siblings of drinking from streams. The taboo is communicated telepathically to the sister every time her brother is about to drink from a stream: First, he will be turned into a tiger and the next time into a wolf. He resists the urge to drink but at the third stream breaks the taboo, drinks and is turned into a roebuck. This allows the story to continue along the theme of sibling love with magical realism embedded in the narrative, but only because it has been countenanced through the symbolic breaking of the taboo, which is the arbiter of the magical situation.

The Grimms’ Rumpelstiltskin was a version of a story that was paralleled in the English Tom Tit Tot. Here the put-upon and imprisoned heroine is aided in her duties of spinning flax by an ‘imp’. But his aid comes with the condition that she will need to guess his name before a year and a day otherwise she becomes his. She eventually hears him yabbering his name beneath her prison window and so on the final night she is able to repeat his name and avoid being taken from the natural to the supernatural. This story is embedded with the taboo motif of ‘not naming’ (a theme returned to below). A supernatural entity imposes the taboo in a form of competition, which is won by the heroine. She has broken the taboo, in this instance, to her benefit.

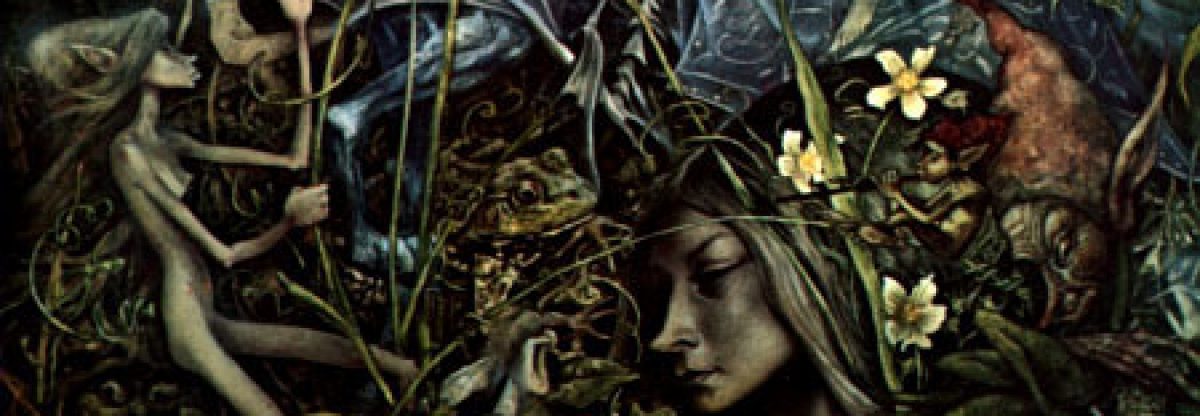

By the time most of these classic faerie-tales were collected by folklorists in the 19th century, they were being recorded alongside less structured types of folklore, which often incorporated localised events and known people (usually from the past but not always) overlain by a story narrative. Taboos are frequently found in this type of folklore, as exampled by the Cornish story Cherry of Zennor, collected by Robert Hunt in 1865. Cherry is a young girl about to enter service in the locality of her home in Zennor. But as she finds herself on a lonely hill she is taken to an alternative reality through the persuasions of the ‘master’; a faerie entity. She finds the faerie world much more to her liking than the one she left and is pleased to stay there under the spell of the master. She is obliged to look after the master’s child and to anoint his eyes each day with an ointment, which she is told to never apply to her own eyes. Once she breaks this taboo she is able to see the faerie realm in its completeness and the faeries that ‘seemed to swarm everywhere.’ But she is soon found out for contravening the prohibition and is escorted back to the windswept hillside. Her breaking the taboo had given her temporary cosmic vision, but the price had to be paid in the expulsion from a magical reality.

The magical ointment motif is common in this folklore type, where the human protagonist is most often a midwife who is persuaded to help out the faeries. She is usually given access to the ointment for washing the babies while being warned not to apply it to her eyes. When she (inevitably) self-applies the ointment the realm of the faeries becomes clearly visible. The most frequent punishment for breaking this taboo was to be blinded at a later date when the ability to see the faeries was revealed to one of their own. In some folklore, this is watered down so that the midwife only has her ability to see the faeries taken away while retaining her natural sight.

The many folktales about swan maidens and lake faeries always contain a specific taboo implemented by the supernatural being while living in physical reality. While the swan maiden stories are Europe-wide, lake faerie folktales seem concentrated in Britain and especially Wales. Once again, there is a crossover quality about these stories, where a recognisable environment and a not-too-distant past is overlain with certain classical faerie-tale archetypes and symbology. The standard scheme of the stories is that the supernatural female is lured from her watery existence by a male, either through a ruse or by charm. They are married and will usually have children together. But at some point, a taboo is broken and she deserts her husband to return to the water, which always seems to represent the portal between the physical world and a non-material reality.

The most detailed of these folktales is the Welsh tale The Lady of Llyn y Fan Fach, which though only recorded in the 19th century contains named personages that appear to date the origin of the story to the 12th century. In this tale, a young farmer called Gwyn regularly frequents Llyn y Fan Fach, where he pastures his cattle. One day he sees a golden-haired woman, combing her locks and using the lake as a mirror. He woos her and she agrees to marry him. But there is a faerie taboo attached: “Silver and gold cannot buy me. Your love is beyond price so I will marry you and live upon Earth with you until you give to me three causeless blows. The striking of the third blow will be the breaking of our marriage contract. I will leave earth and we shall be parted forever. Do you accept?” He does.

Their marriage prospered and they had three sons, but inevitably the three blows were dealt over time, all as accidents: a playful flick on the shoulder with a glove, a tap on the arm and then a third touch when the faerie wife displays joy at the funeral of a neighbour’s infant. She explains that she still sees with the eyes of the Otherworld and that her joy was that the child had transcended the pain and suffering of mortality. But when the third blow is struck she returns to the lake, with her dowry, and disappears below the surface. Distraught, Gwyn follows her, drowning himself in his grief.

Once again, the taboo motif is central to the narrative arc of these folktales. It always represents the jointure between the physical and the metaphysical, and its breaking will sever whatever link has been made between the two. The taboo appears to be a coded message embedded in the folklore, which is perhaps purveying the idea that any interaction with a metaphysical reality has to have a subsequent consequence. The taboo is the key that locks or unlocks the door joining the natural with the supernatural.

More Folkloric Taboos

The taboo was evidently an important element of many folk tales but it is also a vital part of many folk beliefs existing outside structured tales. These beliefs often manifest in anecdotal folklore, where the lore doesn’t need a story loop. One long-standing folk belief was that mortals should not consume faerie food or drink if they ever found themselves in a faerie reality. This was a taboo – to break it meant to leave the physical world and stay in the faerie Otherworld. It is a motif that can be dated back to the 12th century at least, when the chronicler William of Newburgh recounted a story told to him by ‘a reliable person’, where a somewhat inebriated horseman comes upon a prehistoric burial mound known as Willy Howe (Humberside), at night only to be drawn into it via an opening, where he finds a band of faeries in the midst of a revel. He joins in, but when handed a silver goblet to drink from he remembers the warnings against consuming faerie food or drink (evidently a well-established tradition as early as the 12th century), and threw out the contents before making off with the goblet.

The taboo against ingesting anything from the faerie world found its way into many of the 19th- and 20th-century folklore collections. WY Evans-Wentz collected anecdotes with the motif throughout the Celtic world in the early 20th century. In Brittany, the faeries were frequently associated with the dead and if a mortal consumed offerings of food when inhabiting their world, s/he would have to stay there. And a seer in County Sligo told Evans-Wentz, “that once the faeries take you and you taste food in their palace you cannot come back. You are changed to one of them, and live with them forever.”

There is also a prevalent motif of the faeries not liking to be named. This has resulted in the faeries being euphemised with tags such as ‘The Good People’, ‘The Other Lot’, ‘The Fair Folk.’ The motif comes from faerie-tales such as Tom Tit Tot, but it is retained within folklore as a general taboo: the faeries do not want to receive human appellations. Evans-Wentz found the majority of people in all the regions he visited reluctant to name the faeries as such. In Wales, the term was usually the Tylwyth Teg (Fair Family) and several testimonies collected by Evans-Wentz suggested that as long as they were euphemised as such they would remain on good terms with humanity. Too much investigation into what they really were was likely to invoke their hostility.

This feeds into the folkloric idea of the faeries requiring privacy. They usually liked to choose their own time of interaction with humanity and often dealt retribution on those who pried too deeply into their affairs. They lived in a different dimension and it was private, with taboos to protect its autonomy and to ensure a limited transaction between the natural and the supernatural. These taboos are everywhere in the folklore. But where are they coming from? What is generating them as essential elements in so many faerie-tales and in much of the folklore? What do the taboos mean?

The Coded Meaning of the Faerie Taboos

19th-century proto-anthropologists such as W. Robertson Smith, Sir James Frazer, and Robert R. Marett, applied the word taboo mostly to the religious customs of pre-industrial indigenous peoples. For them the taboo acted as a socio-religious code, most  often used to control access to the supernatural. Sigmund Freud adapted their ideas to compare mentally ill patients in early 20th-century Europe to indigenous people, and he retained the colonialist language in his primary thesis on the subject: Totem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (1913). Freud suggested (like his predecessors) that indigenous societies were ‘degenerative’ through their inclusion of magic in everyday life. They were delusional and the delusion was kept in check partly through the elites controlling access to the source of the magic by imposing taboos – prohibiting general social inclusion into Mysteries. Freud compared the indigenous mindset to the ‘neurotic’s’ disorder. The ‘neurotic’ is unable to assimilate the social taboos against breaching ‘normal’ behaviour and will develop according behaviour patterns, usually described as mental illness.

often used to control access to the supernatural. Sigmund Freud adapted their ideas to compare mentally ill patients in early 20th-century Europe to indigenous people, and he retained the colonialist language in his primary thesis on the subject: Totem and Taboo: Resemblances Between the Mental Lives of Savages and Neurotics (1913). Freud suggested (like his predecessors) that indigenous societies were ‘degenerative’ through their inclusion of magic in everyday life. They were delusional and the delusion was kept in check partly through the elites controlling access to the source of the magic by imposing taboos – prohibiting general social inclusion into Mysteries. Freud compared the indigenous mindset to the ‘neurotic’s’ disorder. The ‘neurotic’ is unable to assimilate the social taboos against breaching ‘normal’ behaviour and will develop according behaviour patterns, usually described as mental illness.

Franz Steiner consolidated a lot of this anthropological and psychological data but argued, in his 1956 book Taboo, that the taboo was not exclusive to preliterate societies but was alive and well in the industrial West. Steiner separates religious and political taboos from those that appear to be socially sanctioned and appear organically. But he makes the important observation that there appears to be a core attribute to most taboos, in that they: “have been originally inspired by awe of the supernatural, and that they were intended to restrain men from the use of that of which the Divine power or powers were jealous.” Taboos were devices that helped keep the supernatural from being too accessible. They were warning signs.

These writers seldom touched upon the taboo motif in faerie-tales or folklore despite its ancient presence in the stories. As a folklorist, Evans-Wentz was perhaps more able to consolidate the anthropology of his time with his own insights into the folklore and the living faith in faeries at the beginning of the 20th century:

“Irish taboo, and inferentially all Celtic taboo, dates back to an unknown pagan antiquity. It is imposed at or before birth, or again during life, usually at some critical period, and when broken brings disaster and death to the breaker. Its whole background appears to rest on a supernatural relationship between divine men and the Otherworid of the Tuatha De Danann; and it is very certain that this ancient relationship survives in the living Fairy-Faith as one between ordinary men and the fairy-world. Therefore, almost all taboos surviving among Celts ought to be interpreted psychologically or even psychically, and not as ordinary social regulations.”

As the taboo survived in folklore for centuries it suggests the motif was central to understanding the relationship between the humans who were the main elements of the stories, and their relationship to the supernatural world, regularly manifested through the agency of the faeries. The taboo motif was most often included at the intersection between physical reality and the supernatural. This could work both ways, even in the same story; so whereas Oisín was a part of the supernatural world when he broke his first taboo, his second taboo was committed in consensus reality and closed off his access to the Otherworld. Launfal also closed off his access to the non-physical world by breaking his taboo, and Cherry of Zennor’s chance of staying in the faerie Otherworld away from the harsh realities of her physical life was curtailed when she broke the ointment taboo. These taboos represent the marker-points in the stories where there is a breach between the physical and the metaphysical. The actuality of such a breach is coded in the taboo, which expresses a real transcendent experience in the metaphor of language in a story.

The flat stone Oisín stood on, despite it being taboo to do so, is a symbol of the intersection between material reality and non-material reality, illustrated in plain-form in the story where Oisín is able to behold the physical reality of Ireland and the faerie Otherworld at the same time as long as he remains on the stone. The taboo stone is the link between the worlds but interaction with it also marks the central moment of transition from one reality to another. And the lesson is usually that the supernatural world is not something to be accessed indefinitely by mortal humans. There are entrenched cosmic protocols that seem to legislate against the prolonged joining of natural and supernatural. The taboo acts more as a moment than a thing in the stories – contrasting realities and forcing choices on the protagonists. And in the folklore where the use of an ‘ointment’ is the subject of taboo, there is perhaps a clue that there are compounds that can alter a state of consciousness and so facilitate interaction with an ulterior reality. But their use is sanctioned – they are taboo. The folklore seems to project a consistent message via the taboo motif: We are not supposed to access the supernatural. Under special circumstances, access will be allowed but there will always be a price to pay, and this will be arbitrated by the breaking of a prohibition – the taboo. But is there anything to glean from this folkloric message? What are the modern faerie taboos?

In the Fairy Investigation Society’s 2017 census of faerie encounters, there are over 500 testimonies. They are anecdotal and carry no story arc and so it is no surprise there are no taboos in the narratives. Their anecdotal nature does not allow for any heavy symbolic features. But perhaps the nature of the taboo is just operating at a different level in these modern testimonies. The taboo has become the fear of talking about the faeries and thus confirming a belief in supernatural entities. All of the census correspondents remain anonymous and even then many felt the need to reiterate during their testimonies that they were not intoxicated or mentally ill. This is the case in much modern testimony of people who believe they have experienced a faerie encounter. The fear of ridicule, or worse, acts as the socially sanctioned taboo, which may hinder or prevent people from making a disclosure. This applies to most parapsychological phenomena. Our culture has adopted materialism as its primary ideology and anything psi or supernatural is deemed inadmissible and the product of delusion, misapprehension, hallucination or fakery. This outlook permeates all parts of Western society and so a person claiming to have encountered anything supernatural risks placing themselves outside of accepted, conventional social-norms. This is especially the case with faeries, who have a peculiar niche in the supernatural hierarchy, mostly due to their transition from folkloric creatures to amorphous winged beings in the 19th and 20th centuries. In today’s world talking about encountering faeries has a specific taboo placed on it – the faeries have a particular quality of otherness that is different from other psi phenomena such as UFOs, ghosts, precognition, telepathy etc. There is something deeply subversive about disclosing an encounter with a supernatural life-form that, according to the folklore, appears to have been around for millennia, but which has been marginalised to children’s lore for at least a century. The disclosure has become the taboo that will have consequences for the purveyor, and just as in the tales and folklore this modern taboo is at the intersect between physical and metaphysical.

The taboo motif seems almost to operate as an archetype – a prohibition that is always in place to prevent too much contact between the natural and the supernatural. In faerie-tales and folklore, a taboo-breakage is the means to take a human out of the Otherworld or to take a faerie out of this world. The stories need the taboo key, and the key always ends up locking the door between different realities. Modern faerie-encounter anecdotes have a social taboo placed on them created by a fear of discussing such supernatural interaction, thus stifling any chance to understand them. In all cases, the taboo manifests as an apparently inherent barrier between physical and metaphysical. The breaking of a taboo is the moment where the necessary closure between natural and supernatural is maintained. The coded message seems to be that while we live we can only have limited contact with any transcendent reality. Any transgression of the taboos that hold the contact in place will sever the link – the taboo acts as a metaphysical control-mechanism. From the faeries’ perspective of needing and requiring only limited contact with humans, the taboos have been very effective.

As is the case with every one of your excellent posts, Neil, I could quite easily write a thousand words or so here, because what you have written is so informative and is so thought-provoking at the same time. Instead, I’ll use some iron discipline and write briefly about just one experience that I think might be relevant. I forget the exact year, but I first visited Glastonbury Tor a few decades ago, most likely in the early 1990s. I’d read much about it beforehand, so I was looking forward to seeing this strange, magical place, but even though I do not think of myself as psychic, or no more psychic than the next person, I was taken aback by what I encountered. It was a bright, sunny day and I walked through the field near the highest part of the Tor, where the tower stands. When I got to within about 15 feet of the stile leading onto the steps ascending the Tor, I felt that I could see with my peripheral vision or with my “mind’s eye” a huge concourse of mediaeval tents, banners and pavilions somewhere to my left, just as you might expect to see in some high budget, fantasy film about King Arthur. When I turned to look, these structures were not there, of course, but at the same time, I experienced the absolute certainty that if I were only to recite the magical formula out loud, and walk in the prescribed fashion, I would physically enter another physical reality in which the huge arrays of tents and banners, peopled by magical beings, lay sprawled but highly animated in the Summerland fields. No, I had absolutely no idea of what this formula might have been, but I remain certain that there *was* one.

LikeLiked by 4 people

Thank you D. I think you’ll be in plentiful company with this type of experience at Glastonbury. Your thinking a magical formula is there, but just beyond reach is especially interesting – another way (besides taboo) of the cosmic principles keeping the physical from the metaphysical. Thanks as always for reading…

LikeLiked by 2 people

It was as if the formula were on the tip of my tongue, while I was equally certain that if I performed some movements or steps at the same time, then I’d be able to physically enter this realm. In all the years since, I’ve never had the remotest intimation of what the words or dance steps were, but it was like standing on the threshold of a long-forgotten dream. All your many mentions of taboos in fairy stories brought these memories flooding back and I’m very glad that you understand why I mention my brief tale in connection with this particular post. In my time, I’ve visited literally hundreds of strange locations in Britain and in a few other countries, but I’m pretty sure that my experience at Glastonbury all those years ago is unique. Even to recall it decades later is to feel a strange pang of regret that I couldn’t enter that realm with the banners and tents, so whatever happened that day had a peculiar potency to it. Now I look forward to reading more of your excellent posts, Neil, because apart from anything else, there exists the real possibility that I’ll be reminded of more such experiences.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Sorry to hijack the thread but I was curious to know. what you thought of this book?

The Myth of Disenchantment

Magic, Modernity, and the Birth of the Human Sciences

Jason A. Josephson-Storm

LikeLiked by 1 person

All comments welcome! It’s not one I’ve heard of but will check it out. Do you recommend it?

LikeLiked by 1 person

I definitely recommend it, in the book he shows how many scientists were/are interested in the supernatural and that most people still believe in a world full of spirits.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Brilliant. I will order it. Thanks for the heads up…

LikeLike

Thank you Sue. Your re-post is appreciated as always…

LikeLike

Really interesting stuff. Here, when we say ‘A man’s word is his bond’ we tend to take it with a pinch of salt. In the more rarefied dimensions you are discussing though, words uttered and actions undertaken definitely have binding consequences. We are on training wheels here; Looked after and given allowance. If there is any credence in so called ‘karmic forces’ and the cycling of lives, then there is ‘time’ for us to sink to the grimy depths and slowly pick ourselves up. A broad brush approach, ‘gently’ honing over the aeons. Mistakes and falls are eventually worn away.

To happen across the ‘faerie realm’ or whatever people want to call it, seems to ‘up the ante’. We find ourselves outside the slow grinding process and whatever we say or do carries real weight. All these stories of ‘Faustian’ type bargains seem to hinge on us being urged ‘Just say the words’. We need to voice permission to bypass the safe cocoon that protects us. Denizens of these realms cannot do what they like. We also must agree, and this is where the trickery, word-play and riddles come in to it.

Your discussion about eating the food ‘there’ is an interesting taboo. Some people have the ‘belief’ that the thoughts and emotions we have here, become embodied forms in more ‘subtle’ dimensions; Forms that can have an ‘independent’ semblance of life and can accumulate and gain ‘power’.

‘Food’ in another realm made from the forms found there, would therefor have a very different meaning to the food we use to nourish our physical bodies.

Eating and drinking is one of the most intimate contacts we can have with a world. It seals the deal.

Like the story you told of the horseman who broke the spell when he dismounted and made contact with the earth; It doesn’t seem to take much to be nudged from observer to participant.

LikeLiked by 3 people

Excellent comment – thank you. The concept of ‘food’ having various metaphysical properties in a non-physical context is very interesting, and I only touched on it in this article. It is a common motif in faerie folklore, which I’ll investigate further in the future. And that nudge from observer to participant is, I believe, fundamentally important. Thanks again for reading and taking the time to make such an insightful comment.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Reblogged this on The Sisters of the Fey and commented:

Another fantastic article by Neil Rushton

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you so much Adele…

LikeLiked by 1 person

The taboo breaking being of utmost importance is a kind of fairy mind control. It sets the experiencer up to do everything the fairy says ‘or there’ll be trouble!’ Diverting from the fairy plan is shown to cause misfortune ergo ‘do what I say or else’. They’re more devious than is usually expected.

LikeLiked by 1 person

To me one thing that made the “fairy goes away when revealed” motif popular is that it encodes forbidden relationships, that go “poof” when then become public. Or up in smoke, if found out by the always unexpected Spanish Inquisition.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Insightful as always John – I think you might be right…

LikeLike

I am suspecting this for some time, that the theme is used to justify disappearances, the same way changelings possibly were used to explain several development diseases in children. Good articles on this characteristic of changelings can be found in section III of the book The Good People, edited by Peter Narváez; an excellent online resource is Ashliman’s essay on the subject, online at [ https://www.pitt.edu/~dash/changeling.html ].

On my part, I made some comments on selkies: [ https://forums.forteana.org/index.php?threads/selkies-feminicide.66789/ ].

John…?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thanks for this – serendipity, as I’ve just ordered Narváez’s book. Sorry about the ‘John’… I was looking elsewhere!

LikeLike

A well-researched and most interesting piece. Such a thought-provoking and enjoyable read. Thank you for taking the time to craft this!

LikeLiked by 1 person

The interesting thing about jinn is that they don’t like it when you try to investigate them.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Yes Sakib – it’s a common trope in faerie folklore, which is what I think the taboo motif is all about. Thanks for reading and commenting…

LikeLike

Well there’s lots of similarities between aliens, fairies and jinn, here’s a short summary:

1. They like to appear at night or at the very least after sunset.

2. They like to appear to people that are alone.

3. They seem to manifest in isolated and remote areas especially in nature.

4. There seems to be some sort of link with the phases of the moon but I can’t seem to figure out what the deal is.

5. Some of them like to perpetuate false beliefs such as they created humanity etc. They take great joy in tricking people and making them believe what they want.

6. All phenomena seems to be highlighted in specific areas or hotspots. My theory is that these are areas where there are portals between dimensions and that’s why more activity manifests in those areas.

I would recommend reading some books by Rosemary Ellen Guiley.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also the other thing, they all communicate telepathically with people.

LikeLike

Thank you – I am with you on all 6 points, although number 4 is not something I’ve investigated. I have not heard of Rosemary Ellen Guiley, but will now check her out…

LikeLike